Bob's Your Uncle, but Piotrek is Everybody's Problem

"Collateral Healing" and "Spiritual Leadership" in Lynch's "Elegy for Film"

Personal Reflections

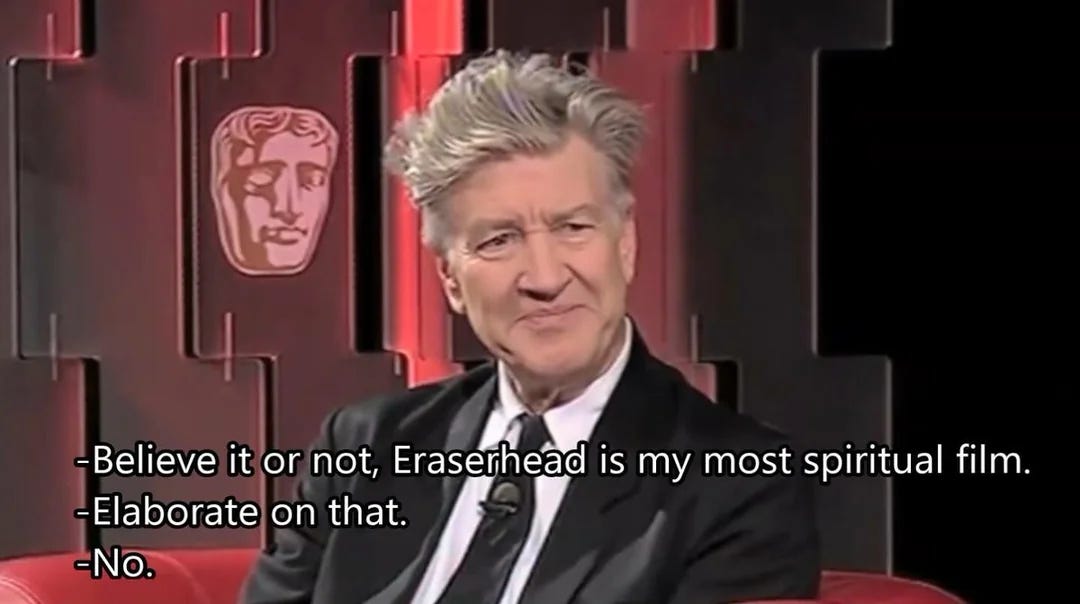

I loved David Lynch for all the reasons everyone does. His humour and humanity. His inhalations and innovations of American Spirits. His manifestation of The Mystery Man, Club Silencio’s MC, and The Man in the Planet. Sailor’s assertion, “This is a snakeskin jacket! And for me it's a symbol of my individuality, and my belief in personal freedom.” His direction of Richard Farnsworth in The Straight Story. His production of the documentary, You Don’t Know Jack, an effort to finally allow his “spiritual brother” Jack Nance to “finish his stories.” And for things like this:

I have come to gripes with how traumatic happenings don’t effect my affect in ways that seem sufficient to pass any kind of Sociopath Test1 because I’m also the borderline Stendahl Sinthome sufferer weeping uncontrollably2 at A Woman Under the Influence. I was in this latter condition on the—itself, increasingly-Lynchia—Toronto Transit Commission 1 Line, on January 15th, crying for the first time in my life over the death of a celebrity, putting the words “Llol, Rando,” in the mouths of imagined onlookers.

Pedagogical Policy Position

For the past five years I’ve been writing a novel of film and philosophy, a grope at praxis well outside what any reasonable party would consider my scope of practice. Early in the process, watching Inland Empire, it occurred to me that if we are to address the Ricouerant horror of history, and stumble through the Night and Fog of the eternal return of holocaustic cylicity, then one fulsome line of flight might be an inquiry into why the vast majority of human history has been predicated on Men Possessing Women.3

Having grown up in Sault Ste. Marie, where the word ‘gay’ signifies not a person’s sexuality but rather a soccer field grown too muddy to play soccer upon, I believe Inland Empire should be required viewing for all pubescent boys in P.E. class.

My colleagues at the Ontario Ministry of Education had, what they called, qualms.

“Must it be taught by the Club Silencio M.C?”

“Can he tone it on down with the hypnotic patter4 of depth and amnesia cues?”

“Afraid not,” I said, “required for sensory anchoring the focal deepener which weights itself, which is to say, itself waits, upon ‘the perfect mystery of love.’”

Fanning through the curriculum, I countered, “Why not replace these eight classes spent learning The Macarena or whatever the pertinent pedagogical movement of the moment may be, and replace it with how to perform The Locomotion in time?”

“Why not replace the deconstructionist curriculum or yesteryear’s moral hand-wringing over biological impeuratives with Lynch’s warning from the lightening of the night sky?”

“Why not simply explicate this fractal novella’s plot5 and themes6 followed by a character study of Piotrek, aka The Phantom, aka Smithy, aka The Mystery Man, aka Bobby Peru, who says things such as:

Now I will tell you something... and I will mean everything I say. My wife is not a free agent. I don’t allow her that. The bonds of marriage are real bonds. The vows we take, we honor and enforce them. For ourselves, by ourselves, or, if necessary, they're enforced for us. Either way, she is bound. Do you understand this? There are consequences to one's actions and there would for certain be consequences to wrong actions. Dark, they would be, and inescapable. Why instigate the need to suffer?

followed by the essay question:

Do you want to be like Piotrek. If so, why? If not, why not?

“For visual learners,” I continued, “an alternate question might be posed accompanied by the following visual aid:

What might entitle a man to leer out at the world as seen below, ’talkin foreign talk’, ’tellin’ loud fuckin’ stories’? If anything—i.e., ‘good with animals and has his way with them,’—consider why snake handlers or veterinarians do not share the same tendency to gobble up the Sue Blues of the world with their gaze.

For further consideration: in terms of taxonomic kingdoms, ‘animals’ casts a fairly wide swath: e.g., ‘cats; chimpanzees; your sister, Catherine, all The Lost Girls prostituted by Phantoms in Łódź, Poland.’

Anyone care to answer in the comments?

How to Pay an Unpaid Bill

David Lynch has that droll quote about Dennis Hopper telling him “I have to play Frank Booth because I am Frank Booth.” To paraphrase Lynch’s response: The good thing is that he is Frank Booth. The bad thing…is that he is Frank Booth.” Empathize though Lynch might, before Hopper had to embody Frank Booth, Lynch had to write him. And you don’t bring a Booth into filmic being without the dire recognition that to some widely-varying extent all of us are blinded by the devil, born already ruined, born Boothians.

Legions of multiplex attendees and those self-indentured into watching Oscar nominated-film would then—to their own varying degrees of regret and remorse— either find something relatable in Frank Booth: for what, in essence, is more human than a need for succorance; or they would have to confront, or worse, completely sublimate, why the Boothian way of being seems so horrifyingly other despite clearly having sprung from an infantile lack universal as needing to be burped, changed, or fed.

Awkward transition here, but my own mother considered Blue Velvet one of the worst movies ever made because she doesn’t like to think there can even be a Frank Booth. And while this position is attractive, it leaves a person woefully unprepared should they find themselves in the Lion’s den of the Piotrekian purview.

She had, however, intuited something the wool-dyed Lynch fan might have been too quick to forgive or overlook. In order to believe there can’t be a Frank Booth, she had to think Lynch was “making this stuff up.” And it’s true that he did manifest Frank Booth. So you could argue that simply Loabing all these ghouls into the psycho-sphere is not exactly the height of artistic responsibility.

If you look at Lynch’s filmography until Inland Empire, he conjures these Tulpas of Mr. Eddie, The Mystery Man, and who could forget The Dumpster Bum, “the one who’s doing it.”

Some meet bad ends; most just cruise on down the Lost Highway of liminality, making a pitstop, perchance, in The Black Lodge; or, on any given night, perhaps your dreams may seem inviting; worst of all, maybe you’re Leland Palmer and they take up residency on The Other Side of the Mirror. The hope is they return of their own accord to the fires of hell from whence they emerged, where they find it comfortable, do a little side hustle recording ads for Mack Weldon underwear and the many sworn-adversaries of timeshare agreements.

Regardless, these men are beyond redemption, and with few Lynchian heroes commensurate to curtailing their own closet creeping to save Dorothy Valens, they usually go unvanquished. (Some die, but the cessation of Frank Booth’s consciousness, juridically speaking, is not exactly a punishment per se.)

In the television review made famous by Lynch repurposing the diametrically-adiposed duo’s downward digits as “Two more great reasons to see Lost Highway” Roger Ebert observed that Lynch needed to stop hanging around with lowlifes. And while it would have been a mistake even then to reduce Lynch to any one policy position—either a Midwestern moralist preaching in a straightforward puritanical tone, or a Pervert in the Pulpit7—from Ebert’s perspective all Lynch seemed to be saying was something to the effect of:

Look, there’s this cold wind blowing through our hearts, the birding cry, the lightning look of malignant laughter c

rackling out of closets, denuding women of human dignity out of mirror curiosity; inhaling nitrous oxide in your home and haranguing you at the porn producer’s party conterminous; insisting to Lula that she really does want it until, in perhaps the most perverse of all these energetic exchanges, she literally comes to believe it.

Writing on Nietzsche’s words from The Gay Science “we others who thirst after reason, are determined to scrutinize our experiences as severely as a scientific experiment—hour after hour, day after day. We ourselves wish to be our experiments and guinea pigs” Quinn Whelehan observes in Abyssal Arrows: Spiritual Leadership Inspired by Thus Spake Zarathustra that

In contrast to a passive acceptance of the immediate, this living science tears apart what appears to be solid, self-standing and given, and throws it under the microscope of doubt and scepticism. Far from being a warm embrace, a comfort and consolation, or a firm ground to kneel in faith, knowledge becomes more experimental and unpredictable—the axe that grinds, the flame that incinerates, the lightning that at once disrupts and illuminates, the dark barren sky before dawn—part revelation and catastrophe, part insight and insanity.

Though seldom sparing the grinding axe, incinerating flame, or disruptive lightning, maybe this is why Lynch offered those ten questions orienting viewers towards an understanding of what was dismissed by many fair-weather Lynch fans as a last straw of inscrutability upon release, but was heralded in 2016 as the best film of the 21st century by a BBC Culture poll of 177 international film critics—Mulholland Drive. After The Straight Story’s warm embrace and the death of his aforementioned “spiritual brother” Jack Nance, he had to tear apart the Piotrekian condensate that had solidified, yet was possessed by the Generosity of Spirit to offer viewers a firm ground to kneel in faith, to offer so little as some speculative consolation given that the cinema is the last lone ontological system relatable to all after The Death of God.

“An accident is a terrible event” but what happens if we “notice the location of the accident?”

“Who gives a key, and why?”

“What is felt, realized and gathered8 at the Club Silencio?”

The accidents have been terrible, but we have noted their locations: right here, buried a posteriorinferior to our hearts.

“The love that engenders creativity” and its “liberating and enlivening power9” has given us a key to understanding the realism of the accidents and yet no solution to their stubborn self-insistence.

And Club Silencio is the Gathering Place, the entry-point, like the ocean of bliss Lynch—a réalisateur e’er there was one—could experience simply by closing his eyes.

If uncharacteristic of Lynch, who of^ refused to ‘describe’ or analyze his own work, to be so prescriptive, perhaps its because those questions aren’t answered anywhere near Mulholland Drive.

Perhaps they are offered only so Grace Zabriskie—who before and after10 paying her visit to Sue Blue was11 Laura Palmer’s mother after all—could provide the answer in what would be Lynch’s final film, Inland Empire.

And now the variation: as Night and Fog warns of war sleeping with one eye open, abrupt-cut to Rabbit Diane warning her roommate Rabbit Rita, “This isn’t the way it was. It had something to do with the telling of time.”

Whores of Hollywood Boulevard and whores of Poland try to tell us, “In the future you will be dreaming in a kind of sleep.”

Nikki Grace is cast in On High in Blue Tomorrows.

Smithy and Piotrek talk loud foreign talk and tell long fuckin’ stories.

Something horrible is happening in Poland.

Almost three uncertain and unsettling hours of all this disparation later it is this parable: hyperpositioned from Another Time, Another, Place and dispositioned from Grace to Grace that catalyzes Nikki into human punctum12 literally piercing celluloid to Get Clear into the alley as her alias Sue Blue, screaming

in the ugliest way she’s capable of, so as to match the male marketplace ugliness and feel the horror of the hole Hollywood Boulevard vagina wall story, so she can look through the whole she’s made in the camera obscura and finally see the palatial glow Roger Ebert and my mother had been hoping to see on the other side.

Twenty years after slouching into all these Phantom Toll Booths where, “It looks just like this except for the light and [we]’re scared like we can’t tell you;” after Diane masturbating tragically over having had Camilla killed, after Alice was stripped naked at gunpoint before Mr. Eddie on what had seemed a Lost Highway through Newmarket past the vulgar outlet males—

With her dissolution of negative force, her full identification with faith, and her humanizing payment of the bill of fellow feeling that we all owe to each other, the cycle of creativity is completed. […] With the dissolution of the Phantom, all the dark worlds that have been evoked become filled with light. What was bound is now liberated, and the Lost Girl stops crying. In a burst of non-locality, Nikki crosses a threshold from the world of the Rabbit Room into the world of need in which the Lost Girl has been incarcerated, gives her a tender kiss of release from her situation, and we discover that the Lost Girl’s Room has changed. With Nikki’s freedom has come a larger sense of human responsibility that has nothing to do with her own benefit; it is collateral healing, to coin a phrase.13

The baptismal elegy concludes with a playful ode to all that Lynch hath wrought. As the Bible’s New Testament affirms its Old, Alice from Lost Highway is made whole herself, Rita (rather than Camilla?) from Mulholland Drive blows Nikki Grace a kiss, The Log Lady works a jigsaw—and then the final puzzle piece: a superimposition of the slight smile Grace Zabriskie’s visitor had offered Nikki in the beginning when she assured her, “Actions have consequences.”

With the dissolution of the Phantom, all the dark worlds that have been evoked become filled with light. What was bound is now liberated, and the Lost Girl stops crying. In a burst of non-locality, Nikki crosses a threshold from the world of the Rabbit Room into the world of need in which the Lost Girl has been incarcerated, gives her a tender kiss of release from her situation, and we discover that the Lost Girl’s Room has changed. With Nikki’s freedom has come a larger sense of human responsibility that has nothing to do with her own benefit; it is collateral healing, to coin a phrase.14

Thus Lynch is no longer the herald of the lowlifes, but “herald of the Lightning”. Appropriate, given how while most productions rent them by the day, Lynch’s kept a lightning machine on set at all times. Never know when you’ll need “the lightning look, the birding cry, awe from the grave15,”-type thing, for as Tim Adalin writes in that same Philosophy Portal volume on Zarathustrian leadership:

The spiritual leader must dignify the always already, dignify the presence of the vital spirit—even if subtle, deep, ready and unready—which courses through bodies, luminous as lightning behind the eyes, inseparable with the lifeworld itself. This is the real encounter with greater-than: a navigation of the course as dance of discernment on the Way: a participation in the ongoing realization of continuity through transformation. For the mystery remains, and the call of our modes of orientation remain, even as inevitable structures rise and dissolve in their time

Lightning is most often a product of Hard Rain, and from the first precipitations and crepitations of “Lynch’s elegy for film; a film after the ‘end of film’, yet one that intimates the possibility of cinema’s rebirth in a digital, egalitarian age,16’ Lynch tells it and thinks it and speaks it and breathes it like Cathy the Feurbachian Vampire from Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction.17

Lynch stands in the lifeworld and trades mysteries like Irish Mickey Ward against Arturo Gatti in Rounds 9 and 10 of their own mythic dance of discernment in Atlantic City, a place where “maybe everything that dies some day comes back.”

Lynch’s Thunder on the Mountain descends more like Zarathustra18’s than Moses’, for “Zarathustra does not call you to model qua mimic his being, he calls you to that indefinable/uncategorizable point that is the overman’s repetition, the point from which one’s difference is perceived as a lightning strike to the human being” but also because Lynch’s, like “Nietzsche’s fiction […] does not split the world into two (our ‘natural world vs. a ‘supernatural world), but rather splits one world from within into two offering us true spirit science fiction.19”

The lightning only looks like it comes from the sky. That’s why Bob Dylan, as he’s Crossing the Rubicon can locate “the light that freedom gives” as being “within the reach of every man who lives” because it is “the Holy Spirit inside.20” Thus Lynch had to lack internally rather than look externally to reflect upon all this dread, this darkness, so that all souls—The Lost Girl and her grieving mother; The Little Boy and his grieving father alike—could plainly see the shining waves illumining the precise particle location of the path back to the palace— some place Inland, someplace inside you, somewhere you can remember.

I’m your guy for lighthearted bantz while everybody’s staring at their feet in the funeral director’s office, e.g., “Spontaneous human combustion, eh? What are the odds of that?”

To the point where an usherly tete-a-tete takes place re: precedential tonalities for interjection vs. deferential modalities for my ejection.

I know that if anyone is regarded with more suspicion than the male feminist, it is the male feminist late to the party, which is most likely a baby shower for a gestating daughter who has forced some last-ditch moral adjustments unwantedly upon him.

“What accreditation have these hypnotists?” they asked. “All hypnotists,” I responded, “are accredited as ‘sinister.”

Sinister Hypnotist P.E. Teacher: “Remember boys! There is no band when dreaming in the dark, making patience prerequisite to keeping The Locomotion in time. Attendre, garcons, this is not something we remember. “Is the sunny day's blueness darkening? Does it fade in the evening to give way to night?” If to see on high in dreams of blue tomorrow is to hold dark patience constant, try to remember the spectrescope of Zabriskie’s visit variegated as green rather than red. And yes, you are getting sleepy, and yes, there will be a test.”

Inland Empire Plot Details:

Inland Empire follows Nikki Grace, an actress cast in a remake of a supposedly cursed Polish film. As she immerses herself in the role, reality and fiction blur, trapping her in a nightmarish cycle of male control and female subjugation.

The nonlinear, dreamlike structure presents multiple overlapping narratives—Nikki’s real life, her performance, and an alternate reality—each reflecting the persistent forces of patriarchy.

Piotrek, Nikki’s controlling and ominous husband, looms over her life, embodying the forces of patriarchy that dictate her movements and decisions. His presence, though often indirect, suggests a possessive grip that mirrors the film's deeper exploration of historical oppression.

The character of the Phantom serves as a spectral representation of male violence and control, appearing throughout the film to reinforce the idea that Nikki/Susan’s life is not entirely her own.

Nikki's journey through the underworld of Hollywood, filled with eerie figures and shadowy corridors, suggests a metaphorical descent into the unconscious fears and desires that shape women’s existence within patriarchal structures.

The film’s climax, which sees Nikki confronting and ultimately reclaiming fragments of her identity through acts of resistance, offers a glimpse of agency amidst the oppressive forces that define her world.

Inland Empire Themes:

Possession and Control: The film relentlessly interrogates the ways in which women are possessed—emotionally, physically, and culturally—by men, both in intimate relationships and within larger societal structures. Nikki’s entrapment within the narrative reflects broader patterns of male dominance.

Cycles of Oppression: The cursed film within the film serves as a metaphor for the cyclical nature of historical violence against women, suggesting that patterns of abuse and exploitation are endlessly repeated across generations and cultures.

Identity Dissolution: The blurring of lines between reality and fiction reflects the way patriarchal forces strip women of their sense of self, reducing them to objects within male-driven narratives.

Hollywood as a Site of Exploitation: Lynch critiques the entertainment industry as a microcosm of broader societal structures, where women are commodified, controlled, and discarded.

Fragmented Time and Trauma: The film’s disjointed, non-linear structure mirrors the fragmented experience of trauma, emphasizing how the past continually intrudes upon the present in ways that defy rational explanation.

The Male Gaze and Surveillance: Piotrek’s controlling nature and the omnipresent watchful figures throughout the film illustrate how women are constantly scrutinized, their autonomy undermined by external forces.

“Gathering is the power, enacted through and as language, which brings human beings, things, and natural objects into relation with one another. While authentic or poetic language gathers entities together in order to hold them in relation with one another, inauthentic language drives them apart.” - The Cambridge Heidegger Lexicon

David Lynch Swerves: Uncertainty Through Lost Highway to Inland Empire - Martha P. Nochimson

Recorso, “‘It is always a great moment in the cinema, as for example in Renoir, when the camera leaves a character, and even turns its back on him, following its own movement at the end of which it will rediscover him.” - Gilles DeLeuze, Cinema 1: The Time Image

“The loss of the daughter to the mother, the mother to the daughter, is the essential female tragedy.” - Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born

“The punctum of a photograph is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me.)” - Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

David Lynch Swerves: Uncertainty Through Lost Highway to Inland Empire - Martha P. Nochimson

David Lynch Swerves: Uncertainty Through Lost Highway to Inland Empire - Martha P. Nochimson

James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Robert Sinnerbrink, Inland Empire, New Philosophies of Film: Thinking Images

Written by the Calvinist Nicki St. John, as fate would have it.

To shore up the Lynch-Nietzsche comparison, consider

’s writing in Abyssal Arrows, “Nietzsche’s artistic skill (say in music and poetry), style, and biography can contribute to us thinking of his work as a ‘collection of ideas’ versus ‘insights from the same vision’ and how Lynch epitomizes an artist likely to be victimized by the slack-jawed rube lacking anything insightful to say and so opting for “It’s so random!” when it is anything but. Or Rose’s “Nietzsche was capable of incredibly allegory, metaphor, description, and the like, and this was actually partly a curse, for it made it easy to latch onto his best written parables (while ignoring the rest).” And how many without having seen Inland Empire and perhaps having fallen asleep at a midnight screening of Eraserhead think they know what Lynch is all about: backwards talking dwarves, black coffee, and pie.*Taking a mild risk here with the concert version so headphones on, ideally have an equalizer at hand, and etc.*

In the following few posts I will share excerpts on Lynch’s Los Angeles Dream trillogy drawn from both The Introductions and another work in progress on how the death of Jack Nance informed all of Lynch’s subsequent work, but particularly the Dumpster Bum scene in Mulholland Drive.

I enjoyed this quite a bit, thank you!