What the Broken Glass Reflects

Counterfactuals and Conditionals in the Changing Lyrics of Bob Dylan - An Excerpt from "Time and Propinquity"

TIME AND PROPINQUITY, from Montag Press and ghosTTruth, is an anthology on the broad subject of Time where fiction and philosophy come together to create a unique third thought. This essay—originally presented at The World of Bob Dylan Conference at the University of Tulsa’s Dylan archives—appears alongside contributions from Walker Zupp, Jin Choi, Dr. David Mathew, Andrew Brenza, Brandon Gallaher, Gabe Boyer, Joshua Hansen, Cassandra Passarelli, Jonathan Oliver, and others!

Excuse me, ma'am, I beg your pardon

There's no one here, the Gardener is gone

- Bob Dylan, Ain’t Talkin’

Part 1: Born In Time

From If Not For You to If Tomorrow Wasn’t Such a Long Time many Bob Dylan lyrics contain conditional or if clauses. Dylan’s own mythology further establishes a liminal world in the unreal conditional, i.e. “If we were different people, we could…” He replaces his middle-class upbringing with Woody Guthrie’s. RENALDO AND CLARA projects by colour schema and strata loves Going, Going, Gone differently. In Brownsville Girl, the titles of Gregory Peck films await the narrator’s memory in uncertain states.

As Dylan interlocutes his work by re-orienting past and futural tenses in familiar lyrics, conditionals and counterfactuals escape philosophical and grammatical parameters to consequent themselves with real-world dimensionality. It’s as if Dylan, foreseeing his 60-year career, built literal escape clauses into his songs. In the year between Blood on the Tracks and The Rolling Thunder Revue, the loved object in If You See Her, Say Hello no longer might be “in Tangiers,” but now in “North Saigon.” We don’t question this shift, because she was never concretely in Tangiers, she only might have been. As Dylan’s narrator accuses the over-determined waitress across the diner counter(factual) in Highlands, “How would you know/and what would it matter anyway?”

Focusing on songs such as Brownsville Girl and It’s Not Dark Yet, and films such as RENALDO AND CLARA and MASKED AND ANONYMOUS, I’ll illustrate how conditionals and counterfactuals contribute to Dylan’s singularly extra-temporal oeuvre. Then, I’ll consider how changing such lyrics in live performance allows for a performative embodiment of both the subjunctive might-have-been and the what-still-could-be in the foggy web of destiny should the ifs and whens remain indeterminately Born in Time for Bob Dylan and his audience.

On and Off The Record

Let’s begin again with a counterfactual conditional from Standing in the Doorway Version #1 from the Fragments entry in the Bootleg Series. “l know this horse could throw me but it don’t.” The narrator’s horse could throw him off, but what this structure emphasizes is that it “don’t.” By using don’t, the tenses blend to add a certainty unavailable to the grammatical purist: “But it doesn’t,” or “but it hasn’t” would only mean the horse has not thrown him yet. “But it won’t” only anticipates what would be true once the rider’s relationship to the horse has ended. “But it don’t” evokes a sempiternalist certainty of past, present, and future informed by the subsequent line: “The mercy of God must be near.”

What then to make of A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’s apocalyptic travels, “I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests/I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans/I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard” serving as the protasis (condition) for the prophetic apodosis (consequence) , “And it’s a hard rain’s gonna fall.”

Since the hard rain is only “gonna” fall after the narrator has experienced dead oceans and gaping-mawed graveyards, these sad forests are not the linear consequences of nuclear winter. As is increasingly occurring in quantum computer labs where initial states are reconstructed from final states[2], these effects precede their cause. If the narrator has seen dead oceans and been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard and out in front of dead oceans before the hard rain falls, the implication is that time, or cataclysm anyway, is cyclical, calling to mind Nietzsche’s thought of Eternal Return discussed elsewhere in this anthology.

Shifting from eschatological to interpersonal doom, in Highlands, after a testy Waitress accuses him of not reading women authors, the narrator’s “How would you know/and what would it matter anyway?” suggests that regardless of the rationale for her accusation, the counterfactual outcome will be the same: it won’t matter, at least not to the narrator. The fusing of these two simple questions leads to considerably-deeper ones about the inability or unwillingness to understand others’ perspectives in the increasingly-subjective perceptual silos of a relativistic World Gone Wrong. Having heard the narrator is an artist, she demands, “Draw a picture of me.” The narrator replies, “I would if I could but/I don’t do sketches from memory” which based on the subsequent implausible excuses that follow, is equivalent to, ‘I can but I won’t because I’ve already relegated you to the past.’

“Well,” she says, “I’m right here in front of you, or haven’t you looked?”

I say, “All right, I know, but I don’t have my drawing book!”

She gives me a napkin, she says, “You can do it on that”

I say, “Yes I could, but

I don’t know where my pencil is at!”

Brownsville if/else New Danville Girl conflates the narrator’s past relationship and a Gregory Peck picture he can’t remember the name of, alchemizing data concretely-determined as a film title into the qualitative experience of shared emotions blurred by time. Absent its signifier, any Gregory Peck movie might have been seen, as the relationship might have unfolded in many ways other than rupture.

Sad as it may be that the narrator now drives with someone new, by reflecting on his lost relationship, “Strange how people who suffer together have stronger connections than people who are most content,” and his past nature, “there was something about me you liked that I left behind in the French Quarter” Brownsville Girl offers a freedom to reorient if neither relive or reinvent the past, just as, for Martin Heidegger, “temporality temporalizes as a future which makes present in the process of having been.”

While Heidegger’s statement that primordial and authentic temporality has a way of “having been futurally” can be less than wholly intuitive, Dylan’s lamentation of a lost past and an impossible future reveals how futures arriving “through the process of having been” will change our perception of the past, and how the lifelong process of reconciling successive past ways-of-being affords insight into how we might live in the present and in the future, even if “things never turn out the way you had ’em planned.”

The tragedy, of course, is that the lessons of the past are often learned later than the opportunity to benefit from them. The narrator might apply these lessons to a future relationship, but it’s all too possible a future relationship of equivalent value will never present itself. And even should that equivalent value present itself, the new partner (“Now I know she ain’t you but she’s here”) will never be that movie starring Gregory Peck, but only a movie starring Gregory Peck.

Something about that movie though

Well I just can’t get it out of my head

But I can’t remember why I was in it

Or what part I was supposed to play

“That Movie I Saw One Time” – Conditional and Counterfactual Modes in Dylan’s Films

In 1998’s MASKED AND ANONYMOUS, political corruption leaves a power vacuum filled by a consensus-producing television network. Yesterday’s voices of political dissent have been assimilated into the very system they were protesting. Is Dylan even suggesting the counterfactual, ‘If things get much worse they could be like…’ Or is he presenting his argument using the more straightforward first conditional, ‘Travel around this country often as I do and you’ll realize…’

As the film satirizes the dog and pony show Dylan’s career had become by the 80s and early 90s, another claim might be, ‘Even after the recent Time Out of Mind coronation, I’m still not the person you want me to be. I’m the same guy you dismissed as a mumbler and mystifier. Name’s Jack Fate, alias Rambling, Gambling Blind Boy Willie McGrunt.

Oblivious to Fate’s raw and honest performances, the film’s power players—neoliberal hegemony’s hauntological reversionists, perfume marketers, and Spotify curators—bluster about still thinking themselves the arbiters of Dylan’s star image. They can’t reconcile that Bob Dylan is a Never Ending Star because Jack Fate exists free of their flimsy paradigms, in another time, another place. Jack Fate also exists to free Dylan himself from constrictive capsule summaries of what was by then a 35-year career.

Regardless of how artificial or dominant a networked narrative’s trappings, Dylan and Fate can return to the foundational grammar of songs like Dixie or Diamond Joe. Some, like the network’s crew members paying rapt attention may choose to listen. Others may boorishly shout the word ‘Watchtower’ during Crossing The Rubicon’s live debut.

The film concludes with Fate’s powerful monologue describing how perspectives shift but truth and beauty remain ever-present, if only in the eye of the beholder.

Things fall apart, especially all the neat order of rules and laws. The way we look at the world is the way we really are. See it from a fair garden and everything looks cheerful. Climb to a higher plateau and you’ll see plunder and murder. Truth and beauty are in the eye of the beholder. I stopped trying to figure everything out a long time ago.

His final claim is, necessarily, contradictory. By dismissing the big picture’s irreconcilable complexity and embracing subjective truth and beauty, Dylan anticipates the growing individualism required to live in a country then orienting itself towards a near-sighted Project for A New American Century.

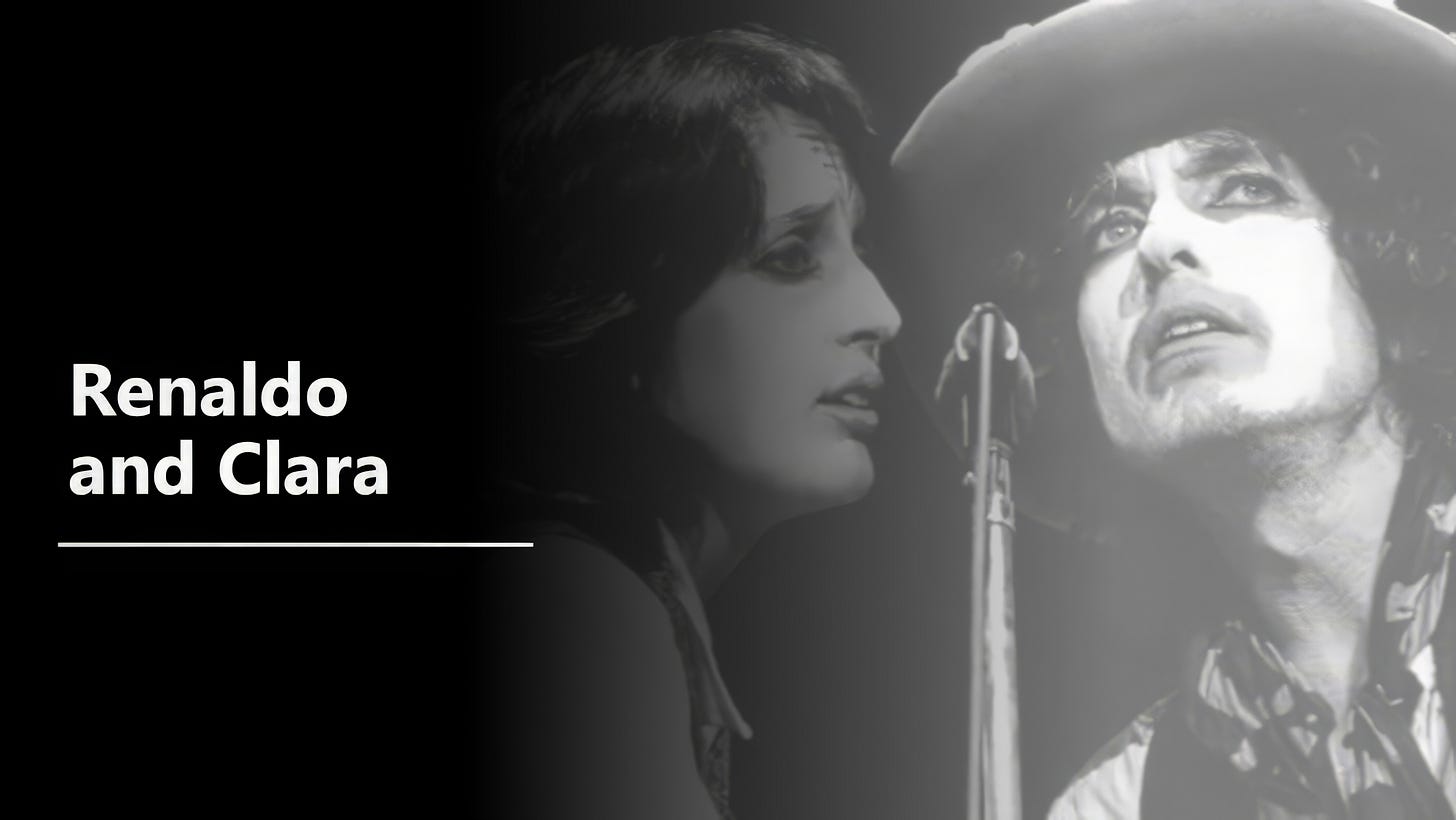

During that same great nation’s bicentennial, Dylan had sought new modes of allocating the counterfactual mood’s temporal aspect in RENALDO, telling Cameron Crowe, then a writer for Rolling Stone that, “I used colors to set moods. Green for the present. Blue for the past. Red for the future.”

Dylan the first- and last-time director dismisses Sam Shepard’s structural efforts to look for what’s present everywhere even as it begins to disappear. Dylan’s road to the past brings his camera to a social club full of old Jewish ladies, Plymouth Rock, and Kerouac’s grave. There’s David Blue playing pinball for what feels like half the movie and reminiscing about the Greenwich Village folk scene. Too much brandy at The Dream Away Lodge and suddenly Joan Baez makes for a beautiful bride-to-be. Harry Dean Stanton, as the outlaw Dylan archetype evoked by Richard Gere in I’M NOT THERE, wins the love of either this Baez or her character after Dylan’s Renaldo trades her for a horse—which is seldom easy on the ego of the horse-traded human being.

Renaldo walks from the barn while his Stanton/stand-in kisses the love from his past, while that most conditional of titles, If You See Her, Say Hello, plays prominent on the soundtrack. The viewer considers what might have happened had Baez not been traded for that horse. But then, that very counterfactual is in the process of playing out on film, a medium that projects a reality only slightly less real than waking life. Baez is, after all, on tour with Dylan. Baez and Sara Dylan debate the literal and figurative content of Dylan’s character in claustrophobic bedroom conflicts. Dylan and Baez don’t only discuss why their relationship ended over Brandy at that brothel, they scream The Water is Wide and Never Let Me Go directly into each other’s mouths in Lowell, Massachusetts and at Maple Leaf Gardens. What might have been is asked to find harmony in a decision made nearly a decade previous, I Shall Be Released.

Perhaps Dylan looks so insanely determined and sings with “the sound of a thunder” that roars “out a warning” not because of the “little green pills” Shepard wrote of, or the black coffee he chugged before performances, but because he was concurrently in the past and future, looking forward and backwards at a Political World where and when “the houses are haunted/the children aren’t wanted, where and when “life is in mirrors and death disappears,” yet knowing all the while that whatever hard rains might (have) prevent(ed) Dylan’s prophesied ships from coming in, Jack Fate the performer has still Gotta Travel On.

As this 4-hour opus explores alternate versions of Dylan’s life and career, its concert footage offered many their first impression of Dylan’s songs rearranged or reinterpreted in ways that challenged expectations. A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall is no longer that dirge for the subjunctive outcome of a nuclear catastrophe, but a frenetically-paced arena rock anthem guided by Mick Ronson’s searing guitar. The new arrangement by Rob Stoner reflects the hedonism of the Fall of 1975, but in a film so concerned with the past it’s practically a Ken Burns film about America’s bi-centennial, moreso than addressing the nuclear tension that was beginning to wane, after Bretton Woods, the validation of Milton Keynes’ and Friedrich Hayes’ economic ideologies, and the nascent global complexity that 1973’s OPEC oil embargo was but the first harbinger of, this Hard Rain seems to predict another type of Fall.

Same Names, Faces Re-Arranged: Lyric Changes In Live Performance

One way of being in the past and future concurrently is to take a song about the conditional future, and make it about the past. Or to take a song that seemed fixed in the past and open it up to the possibility of the future. Dylan may have realized that changing lyrics so rooted in what will, can, or has happened offered a Drifter’s Escape from the overbearing legacy of those capsule summarizers. By calling the pastness and futurity of his lyrics themselves into question, the songs could remain Forever Young But Daily Growing.

These refutals and retrofits, these emergent conditions, consequences, and causal relations afford Dylan’s performances an ecstatic temporality that is richer and more rewarding than anything Paul McCartney or Bruce Springsteen could offer their most dedicated fan.

To begin on an example showcasing Dylan’s frequent application of humour to such changes, consider the multiple variations on the third line of Million Miles’ second verse, originally: “People ask about you, I didn’t tell them everything I knew.” Reflecting the eternal flux of past knowledge and its divulgence, it has been adapted to the present tense: “Well, I don’t tell them everything that I knew.”

A futural tense:

I’d never tell them all that I knew [Nov 08, 2002]

After this line Dylan has alternatively added:

I know that much! [Feb 2, 1998]

Well, I don’t know nothin’ anyway [June 19, 2005]

And, ever evasive:

I just told them a little bit. [Feb 14, 1998]

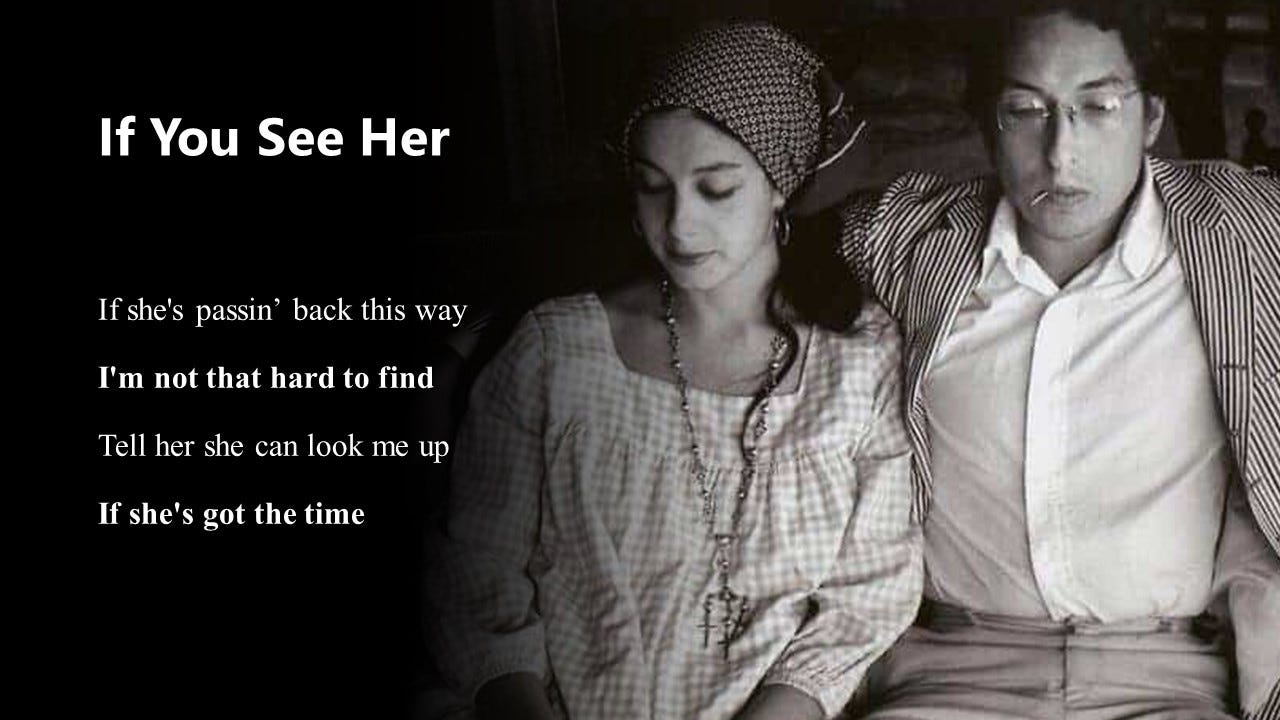

On June 9, 2008, the final verse of If You See Her, Say Hello is altered to reflect an aging Dylan’s evolving relationship to time itself, going from:

to

If she’s passin’ back this way

I’ve got to leave a note

Tell her she can look me up

I’ll either be here or I won’t

The original “if she’s got the time” couples the narrator’s availability with the rueful suggestion the loved object will only look him up only its convenient. The revised lyric, “I’ll either be here or I won’t” instead conveys life’s impermanence and the need to accept what possibilities may come while time remains. It’s no longer the loved object’s use of her (then, ample) time that will or won’t allow for their reconciliation, but the narrator’s dwindling time on earth. And just who is this note addressed to? It doesn’t sound like it’s Estelle anymore, more like a note to someone who’s become so defiled in this world that his own mother, father, or wife would abandon him.

Offers to reconcile with the loved other are often converted into rejections, and vice versa. On the Shadow Kingdom recording of What Was It You Wanted the last line of,

What was it you wanted

Could you say it again

I’ll be back in a minute

You can get it together by then

Transitions from dismissive scorn to entreaty,

You can tell me then.

And while the original narrator reflects on what’s present-in-hand,

Is there something you needed

Something I don’t understand

What was it you wanted

Do I have it in my hand?

when the last line becomes

When you were holding my hand?

the debate over what had been wanted is grounded in a firmer fixity. The original narrator still thought it possible what she wanted might be in his hand. The narrator speaking from his Shadow Kingdom can only remember that she once held his hand. This latter-day narrator considers the same past, but now exists in his own unique present where, twenty-two years after the song’s composition, he admits defeat (she’s no longer holding his hand) while also offering an olive branch (“You can tell me then.”)

In To Be Alone With You from the same Shadow Kingdom performance, Dylan all but begs, “I know you’re alive/and I am too/my own desire is to be alone with you” if “only for just an hour” transforming a song once about the pleasures only found in the present into a paean for what might still be in the dwindling remnants of the future. What follows is essentially an entirely new song that interrogates the past in search of some certainty regarding the present.

I’m collecting my thoughts in a pattern

Movin’ from place to place

Steppin’ out into the dark night

Steppin’ out into space

What happened to me, darlin’?

What was it you saw?

Did I kill somebody?Did I escape the law?

Got my heart in my mouth

My eyes are still blue

My mortal bliss

Is to be alone with you

The new narrator is mired in so much Mixed-Up Confusion he needs to know whether the law has presently got him or not, evoking an uncertainty readable in the conditional spirit as, “What would have happened to me, darlin’?” or “Could I have escaped the law?” These—along with lines like “I’m collecting my thoughts in a pattern / Movin’ from place to place” suggest he’s simultaneously ruminating upon “what the broken glass reflects” and pursuing forward (if fruitless) momentum between one station in life and the next. This creates a devastating through line connecting disparate times and emotions: the revelation that his eyes, responsible for what he’s seen of the past and all he’s subsequently seen, regardless of the grotesquerie of cellular regeneration, are still blue. And should she return, his eyes might convince her that the same can renew.

Being-towards Ecstatic Temporality as a Dylan Fan

This performative bridge between the past, present, and future can only exist if fans continue to cross it however. Prior to seeing Bob Dylan perform at The Beacon Theatre in 2018, my late friend Iain Gardner gained a deeper understanding of Visions of Johanna by visiting the crummy little hotel over Washington Square where it was written many years prior to his birth. Countless teenage Dylan fans grasp the Revelations Blood on the Tracks can only prophesy in the apocalypse of their first breakup. Saps such as myself laugh til tears when hearing a single word from I Threw It All Away changed in concert.

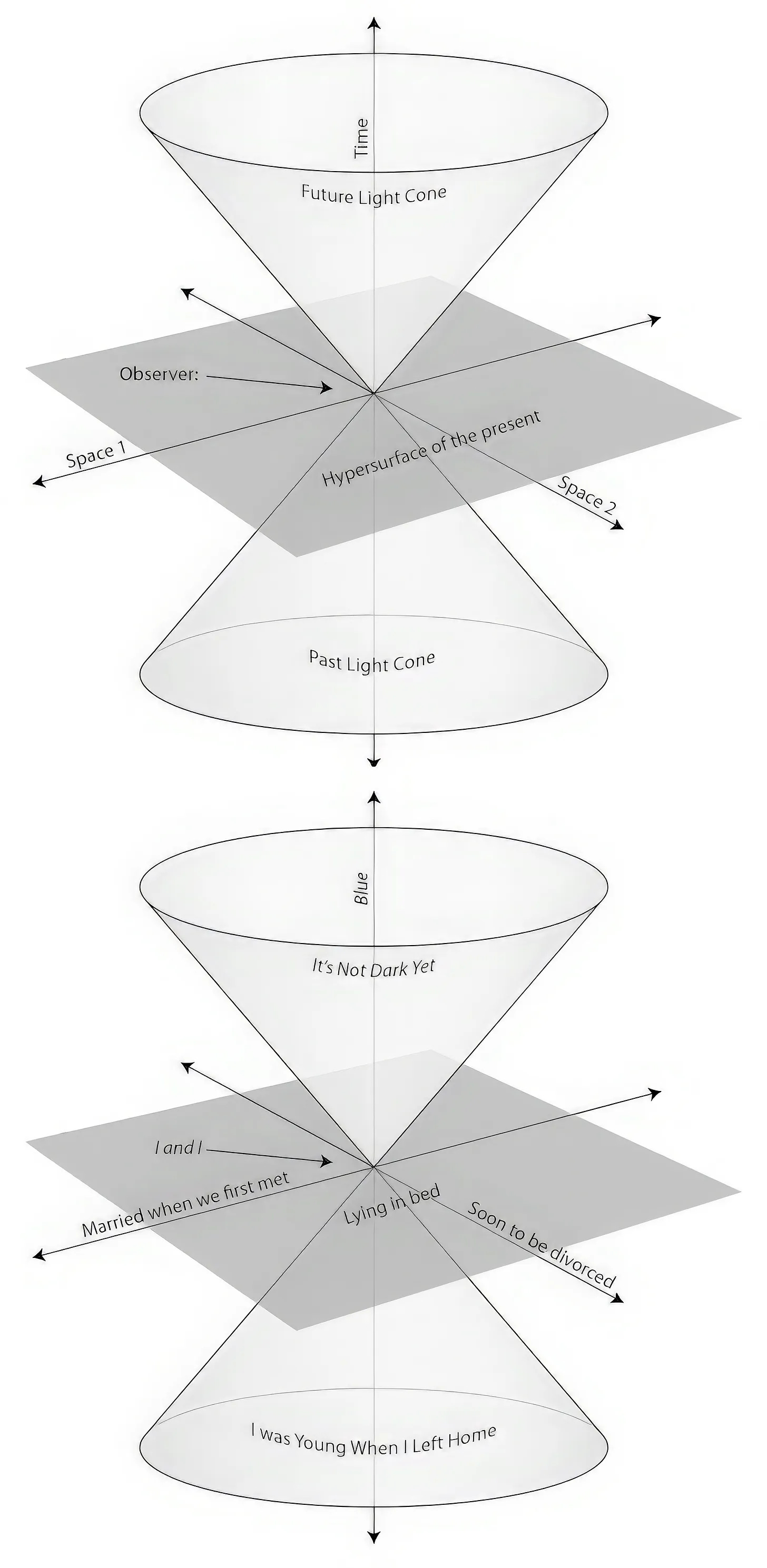

The (thus far) Never Ending opportunity to reassess Dylan’s work through our own changing contextual frames seems to offer fans a some eternalist block of musical Minkowski spacetime to intersect with what Bob Dylan, this “Being of beings,” makes tangible through words and melody of “what is permanent in Becoming.”[8]

It is not enough to repeat what has been handed down to us, what has been given as our tradition, our culture, our history. We must learn to repeat differently, so that what has been can be transformed in such a way that it speaks to us from the future, rather than being simply a dead relic of the past.[9]

Quantitative Proof

With even authorial credit entangled up in blue as Dylan elides authorial responsibility, the capable listener, freed from the constraints of subject-object/artist-audience relationship, finds their own observational efficacy the protasis of the sentence, “If Bob Dylan didn’t die in a motorcycle accident, it’s because we needed him more than Janis Joplin or Jim Morrison.” As offer waves echo back from times’ distant shores, the listener in the hour of deepest need is also the apodosis of, “Because a fan threw a crucifix on stage, Bob Dylan was Saved.”

“If Bob Dylan then appeared at the Vineyard Christian Fellowship, Greenwich Village, or in Norman Raeben’s art class expecting something, and if Jo♺n St♺mb♺ugh wrote that ‘Teleology is also a form of causality; it also leads to all things being firmly knotted together,’ then maybe it’s because he was appearing for us?”

This essay was originally presented at the World of Bob Dylan Conference at the Bob Dylan Archives in Tulsa in 2023. Stay tuned for Part 2 both on The Causal Tentacle and at the new ghosTTruth Substack.

[1] Minkowski, H. (1908). Die Grundgleichungen für die elektromagnetischen Vorgänge in bewegten Körpern. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse, 53–111.

[2] Paris, M. G. A. (2009). Quantum State Tomography. Reviews on Modern Physics, 82, 3045–3061.

[3] Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, Harper & Row, 1962.

[4] Bob Dylan stage talk, Warfield Theatre, November 1979.

[5] Michael Shannon, Jennifer Lebeau & Luc Sante, Trouble No More Q&A, NYFF55

[6] Lebeau, Jennifer, director. "Trouble No More." Grey Water Park Productions, 2017.

[7] Sante, Luc, and B. Clavery. Revisionist Art: Thirty Works by Bob Dylan. Illustrated by Bob Dylan, Harry N. Abrams, 2013.

[8] Heidegger, Martin. Nietzsche: Volumes One and Two. Translated by David Farrell Krell, HarperCollins, 1991.