The Timekeepers of Eternity

An Interview, Eventually, In Due Time, with Filmmaker Aristotelis Maragkos

As Sri Chinmoy could describe my relationship to Stephen King, “You can only hate someone whom you have the capacity to love, because if you are really indifferent, you cannot even get up enough energy to hate him.” As I wrote for HTML Giant in 2014,

Like many writers my age (31), I probably wouldn’t be one if it weren’t for Stephen King. At 16, finding the idea of short story writing woefully unambitious, my early attempts at novels were thinly-masked Stephen King impersonations. Based on the malodorous work that turns up in self-publishing, writers’ workshops, and slush piles, I’m not alone in that my first fictional efforts reeked of The King.

As I began to read ‘better’ books, King became unpleasant for me. His heavy-handed foreshadowing, his loose women who invariably wore, “fuck me shoes,” the wise-ass protagonist who was certain to chummily say “Fuck you and the horse you rode in on,” at some point. It’s not that I wanted to outgrow Stephen King. I wanted to continue being entertained by him, comfortable in the knowledge that a new book was never more than a few months away. But a 1-2 punch of the mentally-handicapped Duddits character in Dreamcatcher (*shudders internally*) and the baby-talk that makes up the second half of The Dark Tower series sealed the deal. Since that time I have tried and most often failed to read new Stephen King novels. I did get through Under the Dome, the high point of his later work. I got halfway through 11/22/63 before literally saying out loud to myself, “What am I doing this for?”

My petulance stems from the age-old trauma of knowing I can not be the same as I was before. Time ate Augustine’s Childhood, after all. A child’s enthusiasm for Richard Rabbit will be taken by time. Time ate The Thousand and One Nights. Time eats the law of conditional probability. Time ate Bernoulli and De Moivre. Time ate the dark ages. Time eats The Discourse Upon the Method. Time eats Yuval Harari and Klaus Schwab. Time eats all our constants and all our constraints. Time eats the objects of sense. Time eats the transcendental conception of reality and the faculty of judgment in general. Time eats reciprocal causality. Time eats every cosmological proof. Time eats the internal sense, our intuitions of self. Time eats all our analogies of experience. All the more reason why you:

My grievance is that in the absence of the past, there’s no analog to the immersive wonder I experienced when Stephen King books served as The Talisman I needed as a teen. When feeling completely alone in the world, not just misunderstood but actively hated by certain thick-browed swarthy cretins cleverly cognomen-hating me “So-gay” I can distinctly remember thinking, “I have these books, and that is sufficient.”

I might have evolved with less bitterness, without shedding these Call of the Crocodile tears had Stephen King been less eager to overpopulate every airport newStand with his abyssal graphomanic output: a chasm that must exist outside of time as it contains supporting characters all still speaking like it was 1978, as well as The Elements of Style lost to the recurrent howl of a Dark Tower of babble.

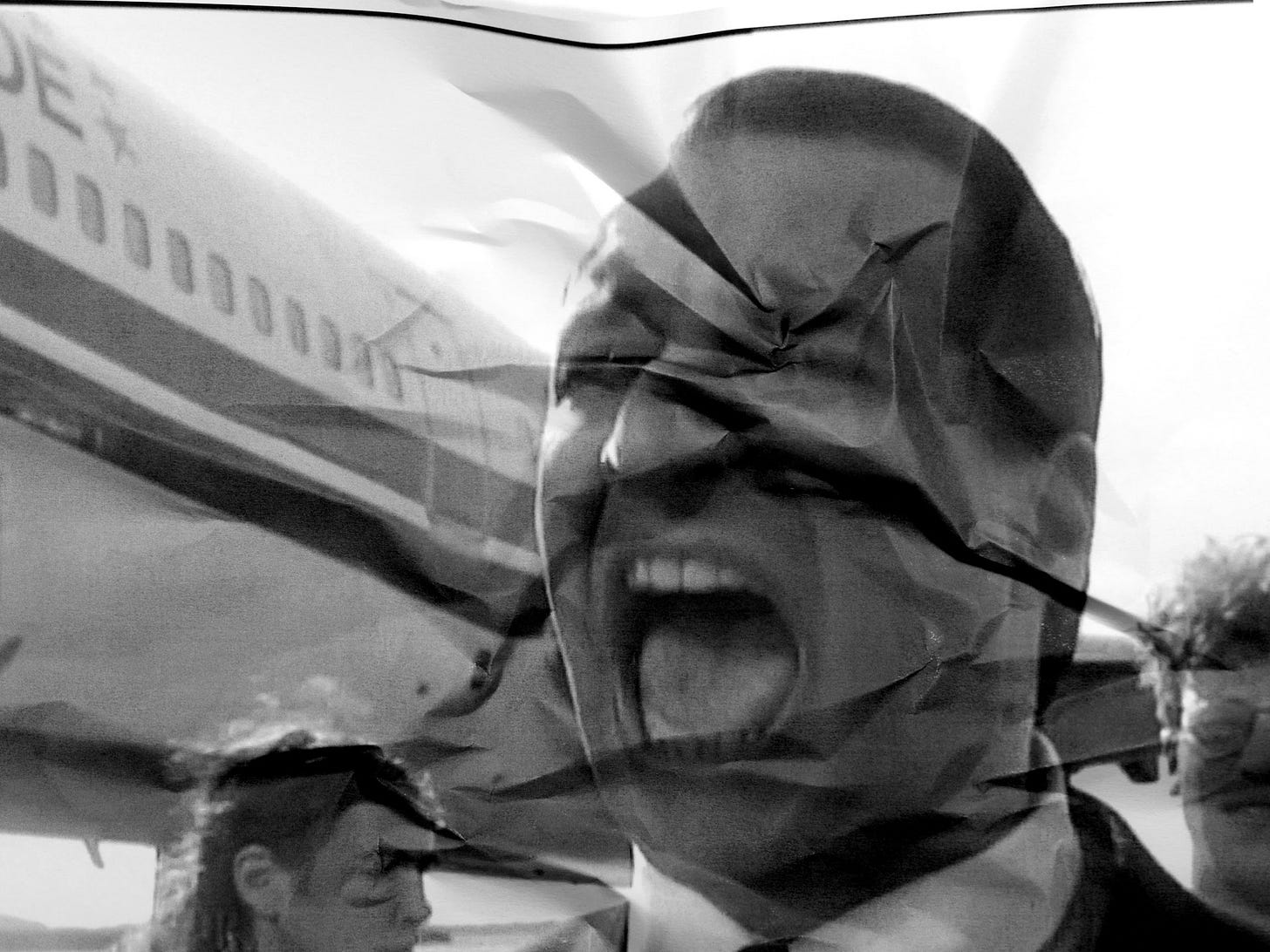

All of this is to indicate why Aristotelis Maragkos’ The Timekeepers of Eternity was such a significant film to me. It is a one-hour distillation of the made-for-tv movie The Langoliers that uses experimental techniques to cut-out and move characters about the screen. It distills the story to its fine essence. More importantly, it changes the ending from the patness that laid the entire Kingdom to Wastelands for me into something true about trauma, the battle for authorship, and to my perception, the unseemly self-certainty of the popular writer.

Mike Sauve: In What Happens To The Present When It Becomes The Past: Time Travel and the Nature of Time in The Langoliers, Paul R. Daniels argues that the passenger’s temporal plight doesn’t fit with eternalism or presentism so much as the moving spotlight theory of time. Did you have any specific philosophical concepts of time in mind when working on this project?

Aristotelis Maragkos: My approach to The Langoliers was always one of inner science fiction, trying to understand the workings of Mr. Toomey’s mind. This excluded any scientific concept of time and space, but examining how this could affect the sense of self. J.G. Ballard once said that he wrote about 'the next five minutes”, and I should coin him as the spatiotemporal approach I used in The Timekeepers of Eternity. I appreciated how a childhood boogeyman could manifest and actually destroy the world. Time folding, existing and being destroyed simultanuasly through the most personalised viewpoint, that of Craig Toomey. But I sound a bit like Bob Jenkins. We cannot escape time and that is all that matters after all.

Mike: Watching your film, I kept thinking what an inspired choice it was, as the writing and acting in The Langoliers is excellent by TV movie standards, but the narrative is necessarily padded to fill a 3-hour run time. What was the initial inspiration for repurposing this particular piece of material?

Aristotelis: Many have contacted me after watching The Timekeepers of Eternity to share that they vaguely remembered seeing parts of The Langoliers when they were young but couldn’t place it in their memory exactly, not remembering the plot or the resolution. I was like everyone else, very young when I first watched it, and was deeply impressed by it. Going back to it decades later I realised my childhood memory had created a different film, a far more personal and terrifying and my repurposing aimed to uncover that.

Mike: The mystery writer Bob Jenkins gets the second most dialog after Craig Toomey. It’s bemusing that we have an MI5 James Bond type, a pilot, a precocious youth, but every important realization is made by this superior writerly species espousing lines like “False logic!” and “I think I found a fallacy in our thinking!” His prominence in your film may have been necessary as his dialog is the principle advancer of the plot; however, I was wondering if you intended to undermine this elevated avatar of cool-headed logic by making his proclamations so prominent?

Aristotelis: There is a battle for authorship that is happening in the film, what rules should it follow? The logic of the mystery writer? The childhood trauma of Mr. Toomey? Or possibly the supernatural senses of blind Dinah? Although for me Mr. Toomey (and Bronson Pinchot’s amazing performance) is the star of the film, I found Bob Jenkins extremely important to express along with the audience the expectations of the genre, so the film could explore beyond them. To answer your question I do not undermine Mr. Jenkins but I believe Toomey doesn’t think much of him.

Mike: You did, after all, change the outcome for the passengers, and by extension the efficacy of Bob’s deductions, by ending the film ‘earlier.’ This aligns the ending with the darker tone of your project, but was it also important that the Timekeepers of Eternity not be beaten by mere mystery righter logic?

Aristotelis: I have no issue with mystery writing, I truly enjoy it. But I cannot see how the Timekeepers could be beaten. How can you tell a child not to be afraid? It is impossible and still we try to do it. We can explain why and it will still not work.

Mike: A cut-out of Toomey speaking spatially obstructs a Jenkins from the preceding shot who had been speaking, making this background Jenkins a component of a ‘new’ group shot of listeners. This strikes me as a revolutionary repurposing of the shot-reverse-shot technique. Can you describe this and other technical processes you employed, and how these influenced the direction of the film?

Aristotelis: I made the film with printed paper which allowed me to spread the sheets on the floor and try to edit scenes firstly in my head. This looked funny from the outside as I would stare at the prints for long time before I made a decision on how to combine them. Applying the shot-reverse-shot to stacks of papers naturally made the characters present in different ways as they are trying to escape the paper materiality I have imposed.

Mike: Your film could be categorized alongside DJ Spooky’s Rebirth of a Nation, in which the impetus was less on retelling the story as calling attention to its biases and shifting the focus onto which characters were really suffering. Similarly, by interspersing the rage of Toomey’s father with Toomey’s own aggressive behaviour, past trauma’s influence on the present becomes the driving emotional force of your repurposed narrative. What sort of thinking about the nature of trauma did you do for the project? Could remixing film or other media be an effective therapeutic tool to symbolically change the past?

Aristotelis: Remixing film can and should be a liberating act, whether that is political, personal or emotional. I don’t believe that we can symbolically change the past, as remixing creates new artifacts that belong to the present. Unfortunately, it takes too long, at least the way I approach material, and to me that was the route into approaching trauma. I shared Toomey’s obsession for ripping paper and discovered a lonely but rich world within the process.

Mike: Beyond it’s refocussing of themes and technical experimentation, The Timekeepers of Eternity very effectively distills the essence of its source material. Certainly it has been more popular with audiences than most experimental films, vague and amorphous as that term may be. Were David Lynch to reinterpret his Dune in such a way, would it not be as commercially viable as any new David Lynch project? Due to the inherent concision of the process, multiple films could also be combined to draw upon each others’ themes. In an age of cultural hauntology where the Snyder Cut trumps Batman vs. Superman in significance, do you see a commercial future for stylized reinterpretations of films that have been semi-forgotten, or even of entrenched classics?

Aristotelis: Commercial future? There are amazing artists working with found footage but I can’t see a path to commercial success. I hope someone proves me wrong but unfortunately there is a difficult path to navigate, within legal pitfalls and personal ambitions. I prefer to look at appropriation films stripped from any goal, existing only because there was no way to stop them. And I do hope David Lynch reinterprets Dune somehow.