A Time (Out of Mind) at the World of Bob Dylan Symposium

This weekend I attended the World of Bob Dylan Symposium to celebrate the opening of the Bob Dylan archives at the University of Tulsa. High points included Krystal S. Reyes’ earnest account of how the death of her husband taught her What Bob Dylan Can Teach Us About Grief and Loss, Steven Thwaits fighting back tears while recounting his interpersonal experiences at late-period Dylan concerts, and Len Cazaly’s interpretation of Bob Dylan, Modern Day Psalmist.

There were low points of course. Wonks gonna wonk after all. A few had the temerity to drone sentences direct from their papers such as, “Bob Dylan, born in Hibbing, Minnesota in…” as if all assembled did not know that Bob Dylan was born in Hibbing, Minnesota in…

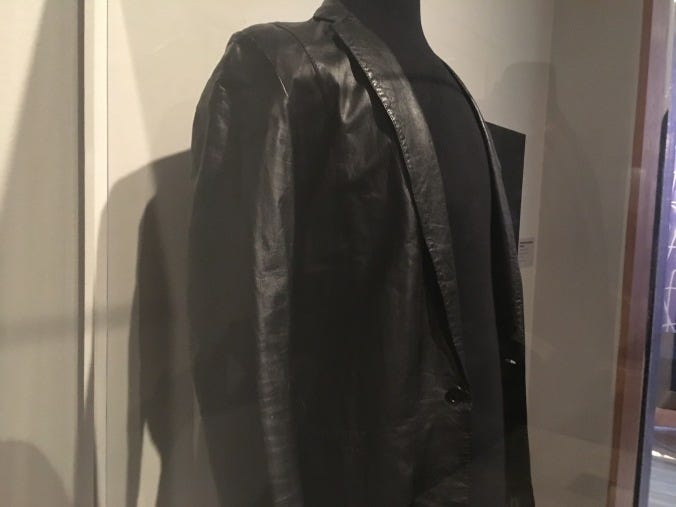

I debated whether or not to write about the conference. It’s not that the display of Bob Dylan’s 1965 Newport leather jacket wasn’t neat. Or that an assemblage of like-minded Dylan fiends was not cause for celebration. My lack of enthusiasm stemmed from my own anti-academic hang-ups. Not being one myself, lacking the discipline to bore down on say An Exploration of Dylan’s Postmodern/Posthuman Educational Philosophies, or even knowing the man possessed such philosophies, I often oscillate between envy and resentment of academic stature. On the envy side of the coin: many, if not most, of these borer-downers got to the heart of some previously-unconsidered idea about Bob Dylan. Resentment-wise: a younger man, an “MA candidate,” as if all we lowly baccalaureate holders aren’t but a few dollars removed from becoming that, spoke at length of his ‘methodologies’ while showing us spreadsheets that detailed data he must have known didn’t particularly matter, but which data was his easiest entree into the Official Bob Dylan Scholars club.

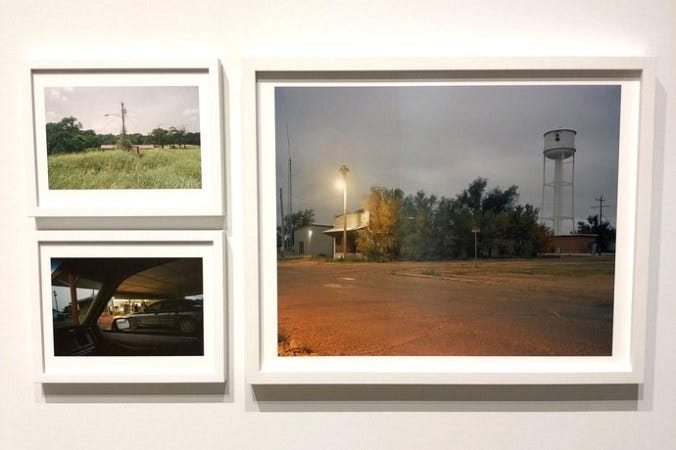

On the second day however, I visited the Philbrook Museum to see an exhibit of Larry Clark’s famed Tulsa series.

I had seen the photo book before, and soon realized the actual prints didn’t hold any particular value over the reproductions. What affected me instead was a photographic exhibit by the former skateboarder and Scientologist, Kevin Smith muse, and My Name is Earl star Jason Lee.

“I like to move and roam and anticipate what lay ahead. And I’m especially inspired by rural America and what lay behind,” Lee wrote on his website. “This other life; the quiet and what remains. These empty places that somehow have that unique cinematic quality to them.”

Lee’s light-saturated photos of the rural ordinary reminded me of something obvious that mid-western fly-over country evokes so consistently—that the past is going away. As Bob Dylan told Bill Flanagan in 2017, “From 1970 till now, there’s been about 50 years, seems more like 50 million […] That was a wall of time that separates the old from the new and a lot can get lost in this kind of time.” Lost is the look of BP gas station tiles laid in 1941. Lost are the bathroom heat lamps in a hundred year old hotel, burning through a few million gigawatts just for the hell of it. Lost are the sun-cracked vinyl interiors of abandoned Impalas. Born, too late it so often seems, in 1983, even I can remember the orange upholstery on the couches of great-aunts born in 1912.

Indulgent, I concede. We all know there’s a time to be born and a time to die and that much must change in the interim. Roger McGuinn wrote those words and on Saturday evening, McGuinn himself sang for a rapt audience of conference attendees. He opened with “My Back Pages”. Older then; younger than that now. Truth was that McGuinn, even in excellent condition for a 76-year-old veteran of the music industry, did seem older now. McGuinn’s tired voice, the same pure instrument that invoked folk music into 1965’s popular consciousness, would occasionally waver, and when it did, I saw a room full of men with their darn hearts a-bleedin’.

And these visions of something beyond nostalgia, beyond the wistful; and these visages of naked pining from men and women who’d cared so much about Bob Dylan in the 1960s that half a century later here they were still trying to figure it all out—they made it all seem too cruel, because like the cinematic quality of the BP tiles, like that other life of our great aunts with their orange couches, Bob Dylan is going to go away too.

So it’s gratefully, maybe desperately, that all the post-humanists, all the Derridaeans, and even all the aspirant spreadsheet wonks look to the Dylan archives to ensure the sun will always shine on Bob Dylan’s fifty million recordings, his epicene leather jackets, his errata of time-encrusted compass blades; we all look to the archives hoping the sun will continue shinin’ through the trees on all that wild genius Bob Dylan has hurled against that desolate wall of time.